Image: 1890 Bartholomew Map of Palestine

by

Dave Westacott

Since the Enlightenment at the latest most Jews in Europe have identified with the national and working class movements. This was driven by the French Revolution, which accorded Jews equality with other citizens.

Even in the period of reaction after 1815, most Jews clearly identified with the oppressed classes. Certainly, feudal and religious decrees ensured that Jews could not work the land or join the growing industrial proletariat, thus being mainly confined to trade and handicrafts. But it would have been unusual for Jews, as a people who had suffered centuries of persecution, not to have associated themselves with the downtrodden.

The reaction that spread through Europe in the mid-19th century drove them into the ranks of those who opposed the existing regimes. They played a prominent role in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, sometimes associated with the middle class, sometimes with the working class, sometimes with the nationalists.

Right up to the end of the 19th century, Zionism remained a small minority in Jewish political life. Of course, in the late-19th-century the French aristocrat Baron von Rothschild had begun buying land for resettlement in what was then Ottoman Palestine. But this remained relatively insignificant, and most Jews who emigrated at the time, largely as a result of pogroms in eastern Europe, did not go to Palestine but to the United States.

The Zionist movement was launched primarily by an Austro-Hungarian Jew, Theodore Herzl, at a conference in Basel in 1897. Herzl’s work The Jewish State (Der Judenstaat) formed the basis of his appeal for a Jewish national home, though his essay Mäuschel also contained stock anti-Semitic tropes and revealed his deep contempt for eastern European Jews.

Indeed, the whole basis of Zionism was premised on the belief that anti-Semitism was ineradicable and that Jews could never assimilate into European society. In this sense, Zionism welcomed anti-Semitism, as it would provide a force driving Jews out of Europe and it was hoped towards Palestine.

Nevertheless, the majority of Jewish organisations remained associated with the left and working class movement and committed to assimilation. As late as 1918, despite Lenin’s correct criticism of its isolationist tendencies, the biggest Jewish workers’ organization in Europe, the Bund, produced a poster declaring “Dortn vu mir leben, dort iz unzer land” (There where we live, that’s our homeland).

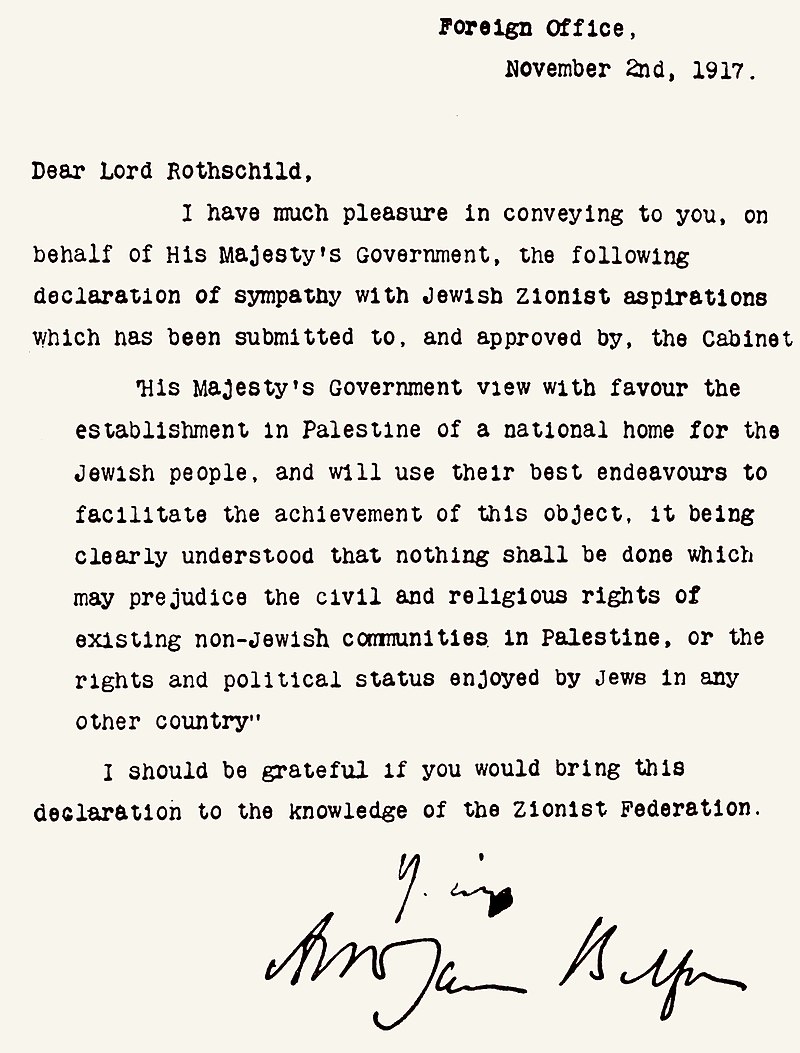

The impetus for Zionism was provided in 1917 by the Balfour Declaration. This was the point around which the alliance between imperialism and Zionism consolidated itself. Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, was no friend of the Jews: in 1905 as Prime Minister he had introduced the Aliens Act, primarily aimed at keeping eastern European Jews out of Britain.

However, Britain was concerned with protecting its assets in the Middle East, above all the Suez Canal and the route to India. This was also the aim of the Anglo-French Sykes-Picot agreement, signed in 1916 and made public by the Soviet government in 1917. Despite having given the Arabs an agreement for a new independent Arab state in return for assistance against the Turks (and having later promised Palestine to the Zionists), this carved up the Arab territories of the Ottoman empire between Britain and France.

In 1914, the Jewish population of Palestine was about 60,000 compared to 500,000 Arabs. Under British Rule, by the 1940s these numbers had grown to 500,000 Jews and 1,000,000 Arabs. (1.)

The original Jewish population had lived peacefully alongside their Arab neighbours for centuries and did not particularly welcome the new influx of Jews from Europe.

The Arab response to the immigration in the early days took the form of anti-Jewish pogroms. Later, in particular in the General Strike and the revolt of 1936, it was clearly aimed against the British. Some flirted with German fascism, but this never really took hold among the Arab population.

The 1936 revolt was brutally repressed by the British, and immigration from Europe continued.

In 1937, Sir Roland Storrs, ex-governor of Jerusalem wrote “enough [Jews] could return, if not to form a Jewish state . . . at least . . . forming for England ‘a little loyal Jewish Ulster’ in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism”. (2.)

The reference to Ulster, loosely northern Ireland, was not accidental. From Irish independence in 1921 to the partition of India in 1947, the policy of the British government to its former colonies had been divide and rule. In other words, boosting religious minorities in order to undermine national independence movements.

This did not just apply to Ireland, India and Israel, it was also applied everywhere from Guyana to Uganda to Malaya.

But in 1939, after the outbreak of the Second World War, the British government was forced into a rethink. It realized that it would need the Arab states in order to prevent Germany from exploiting Arab nationalism to increase its influence in the Middle East and thus threaten the route to India. This change was encapsulated in a 1939 White Paper, and Britain then moved to prevent new European immigration to Palestine. This immediately put it into conflict with the Zionist movement, which subsequently embarked on a terror campaign against Palestinian villages and the British administration. This culminated in the 1946 bombing of the King David hotel in Jerusalem, carried out by the Irgun, led by Israel’s later prime minister Menachim Begin, killing 91 people.

On 14 May 1948 the British announced the formal end of their Mandate and the state of Israel was declared.

The following day, the five states of the Arab League began their invasion of Israel.

In a telegram to the United Nations, the Arab League announced:

“The Arab States recognize that the independence and sovereignty of Palestine which was so far subject to the British Mandate has now, with the termination of the Mandate, become established in fact, and maintain that the lawful inhabitants of Palestine are alone competent and entitled to set up an administration in Palestine for the discharge of all governmental functions without any external interference.

“As soon as that stage is reached the intervention of the Arab States, which is confined to the restoration of peace and establishment of law and order, shall be put an end to, and the sovereign State of Palestine will be competent in co-operation with the other States members of the Arab League, to take every step for the promotion of the welfare and security of its peoples and territory.”

The telegram also declared:

“We are fighting for an Arab Palestine. Whatever the outcome the Arabs will stick to their offer of equal citizenship for Jews in Arab Palestine and let them be as Jewish as they like. In areas where they predominate they will have complete autonomy.” (3.)

The problem for the Arab states was that they lacked a unified command. Furthermore, like most newly independent states, they were staffed largely by British officers. The commander in chief of the strongest force, the Transjordanian army (now Jordan), was Sir John Bagot Glubb, also known as Glubb Pasha.

In an allusion to the early stages of World War Two, when Britain, France and Germany had declared war but mainly refrained from hostilities, he described the Arab League attack as a “phony war”. However, he himself was charged with sabotaging the Arab war effort by issuing contradictory orders 48 hours before the start of the war.

The Nakba

In this period, some 400 Palestinian villages and seven Palestinian cities were destroyed and 750,000 Palestinians forced to flee as a result of the well-armed Israeli terror gangs, often preceded by the British army forcing Palestinians out of homes they had lived in for generations.

On 20 May 1948 the United Nations appointed the Swedish Count Bernadotte to Palestine to act as a mediator. His plan called for Jerusalem to become an international city under no overall control and for the right of return for displaced Palestinian refugees.

Bernadotte was assassinated by the Stern Gang in September 1948, also led by the later Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir.

Since then the Nakba, the catastrophe, the forcing of Palestinians out of their ancestral homes whether in the West Bank or the rest of Israel, has not ended. It is still going on and has reached its high point in the invasion of Gaza.

Of course, since the mid to late 1960s Israel has switched its main benefactor and arms supplier from Britain and France to the United States. And despite the fact that the US has recently become less dependent on oil and gas from the Middle East, it still recognises that an independent Palestine would pose a massive threat to its interests in the region.

The largely feudal Arab states also face a serious problem: they are compelled by their own populations to support the Palestinians; but they recognise that a truly independent Palestine would pose an existential threat to their rule. Their support is therefore equivocal at best.

The war in the Middle East is also threatening to throw the politics of western Europe into turmoil. When hundreds of thousands of people come out onto the street to demand a ceasefire, even the craven pro-Nato leadership of the British Labour Party finds it hard to hold the line and tectonic political plates begin to shift in ways that were previously unimaginable.

For Israel and Palestine, itself, whether we argue for a one-state or two-state solution, the fact remains, any state that privileges one ethnicity or one religion over another cannot be a democracy. An independent, democratic Palestine, on the other hand, threatens the dubious stability of the whole region and beyond.

1. Rennap, Anti-Semitism and the Jewish Question, London, 1942, p. 80

2. Orientations, 1937, p. 404, Anti-Semitism and the Jewish Question, 1942.

3. Palestine Post, 21 May 1948, p. 3.

About:

Dave Westacott is a former journalist and translator living in Vienna.

Whitstable Views: How You Can Help

- Make sure you share and like our articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.

- Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)

- Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going. All of our contributors are willing to engage with you if you leave a comment.

- To all writers out there, we would LOVE you to make a contribution. Read our submissions page for details on how to go about that: https://whitstableviews.com/submissions/

- Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/