Whitstable, Ruby Cunningham, sewage and DFLs

by

It was an unconventional choice of venue for such a romantic gesture, but I proposed to my wife on one of Whitstable’s wastewater outfalls.

We stood hand in hand by the big red metal can at the end of the concrete block and I produced an engagement ring, designed by a jeweller in the High Street. It was a small diamond surrounded by a circle of sapphire splinters, set into white gold. It was modest, classy, beautiful and unique. And so was Sarah.

We both loved the sea. Diving, sailing, swimming or just gazing at it. Both of our jobs were maritime related. It’s how we met. It’s why we loved Whitstable so much.

After she died this summer, her family and friends cast brightly coloured flowers into the sea from West Beach, near our house. A few days later, when sunset coincided exactly with high water, at 8.46pm, I paddled out on a perfect summer’s evening and cast her ashes into the gentle waves. I sat there alone, bobbing gently on the blue plastic kayak, as the sun disappeared behind the Isle of Sheppey, and I cried and cried.

Dissertation

The following day I had agreed to meet with Ruby Cunningham on the beach. It had been arranged much earlier. I wasn’t really in the mood to conduct media interviews but she was an exceptional young woman and I didn’t want to let her down.

Ruby had interviewed me the previous summer. I was one of a cohort of local people who swam in the estuary, who agreed to participate in her dissertation project for her Geography degree at Birmingham University. It was entitled ‘Sick of the Shit’. Ruby wanted to find out if sewage pollution had changed Whitstable people’s relationship with their town and its sea. I had asked her to send me the finished study and, about one year later, she did. When I read it, I thought it was so good, I requested an interview with her with a view to writing a feature about her work.

We met on West Beach in burning July sunshine, just where we had all cast the blooms into the sea for Sarah, a few days previously. Ruby grew up in Tankerton and is a sort of progressive socialist. The nice sort.

I told her what had happened to my late wife and apologised that I was still not on top form. Then I told her about Sarah’s connection to the sea.

“I know, you told me about her the first time we met,” she said gently and we sat next to each other on a timber groyne and proceeded to talk about sewage pollution and her dissertation.

Solastalgia

“I have always been left wing with an interest in Marxist literature—I felt this was more of a moral question,” she told me. “I am fascinated by how capitalism and neoliberalism affects nature.”

She used the French left-wing thinker Henri Levebre’s ideas about the privatisation of urban space and how it changes our relationship with our environment. She used his philosophy to explore how a privatised utility, like Southern Water, had alienated the people of Whitstable from their cherished public asset—the sea. Her findings were both fascinating and tragic.

Local people told Ruby that the coast was key to Whitstable’s place identity and nearly all (86.7%) of about 130 questionnaire respondents agreed that “the sea is an integral part of the local identity”. Many described the sea as the “heart” of Whitstable.

“An overwhelming majority (94.5%) of local sea swimmers agreed with the statement, ‘I feel emotionally connected to the coast,’” said Ruby.

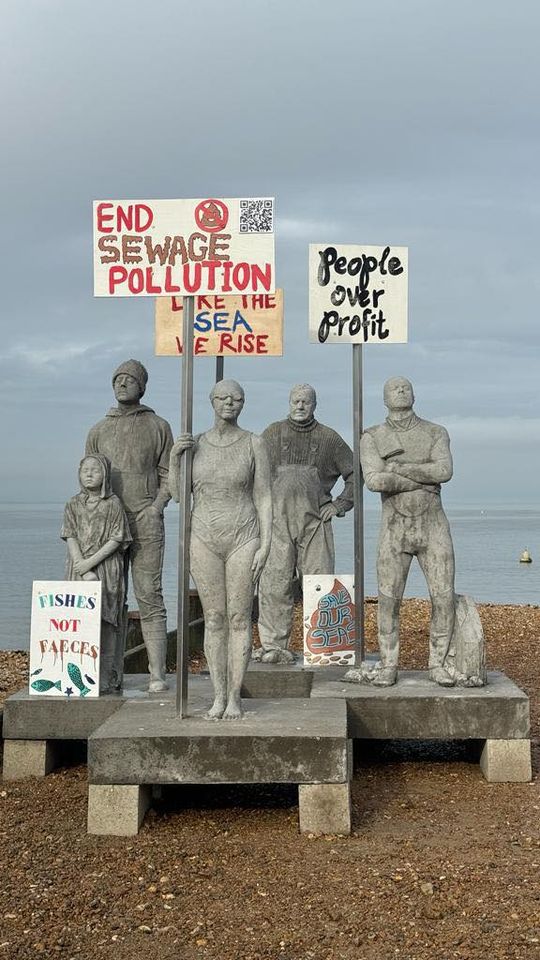

But her study revealed the precious emotional connection to the sea was being fractured by the chronic pollution caused by Southern Water. Frequent discharges of untreated human waste were causing something called Solastalgia, denoting environmentally induced distress or a nostalgia for a once-healthy environment.

People told her that they always thought about sewage pollution whenever they approached the sea. One woman said it had negatively affected her friendships and another said she was considering moving from the town. One man reported that he felt the pollution had poisoned his relationship with his home town. And there were other more subtle findings too.

Down From London

The sewage pollution problem was also causing division and highlighting the issue of DFLs (Down From London) and gentrification in Whitstable.

“There seemed to be an attitude among older residents that they were more accepting of the pollution and they felt uneasy about publicising the problem with papier-mâché costumes—they worried about the reputational damage it was causing their town,” said Ruby.

“This was seen as a DFL problem and tied to gentrification,” she added. And the study revealed another surprise.

“What shocked me most was that the people I spoke to just didn’t know what was going on,” she said.

Those surveyed had no idea if it was safe to swim. Some knew how to find out about recent sewage releases but they were not sure what that meant in terms of public safety in their preferred swimming location.

“Each person had invented their own safety protocol for swimming in the polluted water,” said Ruby.

Some sea swimmers preferred to keep their heads out of the water. One woman stated she only swam when the tide was going out. One man told her he drank a tin of Coca-Cola before entering the water.

Health Risks

“I was really surprised that this was a major public health issue and people were making up their own rules because there was no scientific guidance about the health risks of entering the water,” she said.

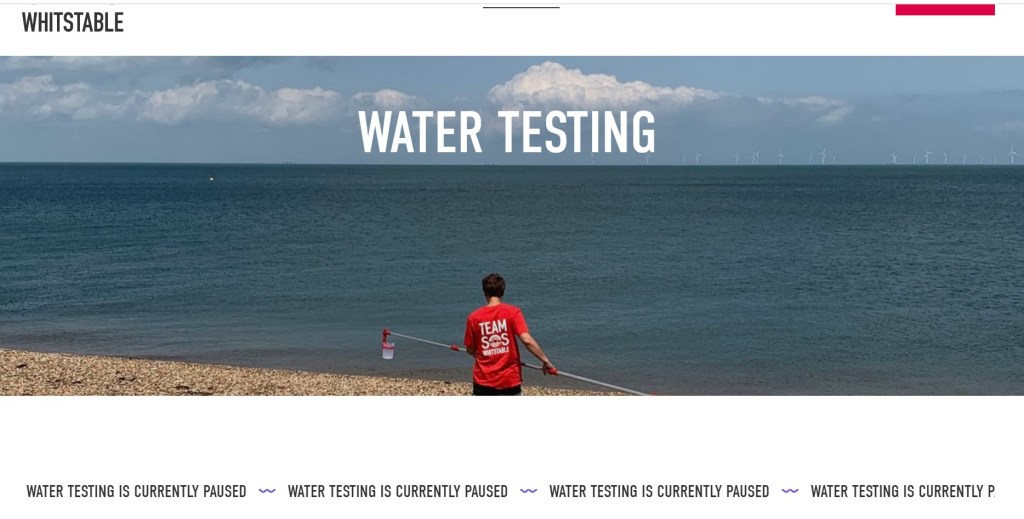

SOS Whitstable stopped testing the water this year after a string of unreliable results and there is still no information at popular swimming locations about bathing water quality. Few take any notice of the Environment Agency official testing conducted (coincidentally of course) only after dry weather and often before significant sewage discharges occur.

Ruby’s hard work serves as a reminder that in a relatively prosperous coastal town heavily reliant on its tourist economy and with an oyster fishery, no one can tell you if it’s safe for your children to swim and play in its bathing waters.

Ruby’s dissertation scored 74%—a first class degree pass. Southern Water are unlikely to be marked so highly while the rest of us suffer from chronic Solastalgia.

“The project has meant I am more conscious of the sea and of the pollution, and it helped connect me to my home place,” said Ruby and as we part, I confess to her that Sarah’s death has had the same effect on me.

Ruby’s dissertation is available to read here.

Stuart Heaver

Professional journalist and author.

New book was published by The History Press on 23 June 2022.

South China Morning Post – The Independent – Hong Kong Free Press – Who.What.Why. – Byline Times – Fragrant Harbour – New Lens International – Daily Telegraph – Post Magazine – Sailing Today

Follow @stuartheaver on Twitter

Whitstable Views

How to use it!

- Make sure you share and like our articles on Facebook and Twitter/X, and whatever other social-media platforms you use. Join us on Facebook here: @whitstableviews

- You can read and contribute articles for free but in order not to miss any, please subscribe to get regular free updates.

- To do so, press the “Subscribe” icon on the bottom right hand corner of the screen. This will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down then reappears at you move it back again!)

- Please engage by leaving comments on the website, rather than on social media. Let’s get a debate going. All our contributors welcome the chance to engage with YOU.

- To all writers out there, we want to hear YOUR views too, so do submit your own articles. Read our submissions page on how to do this: https://whitstableviews/submissions/

- Finally, to keep Whitstable Views alive and independent please donate if you feel able to do so. As little as £1 would help. Details are on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate