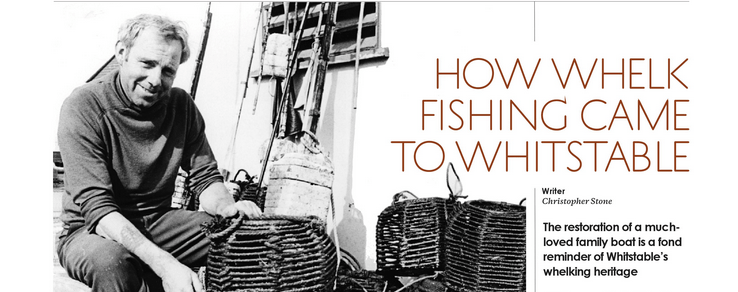

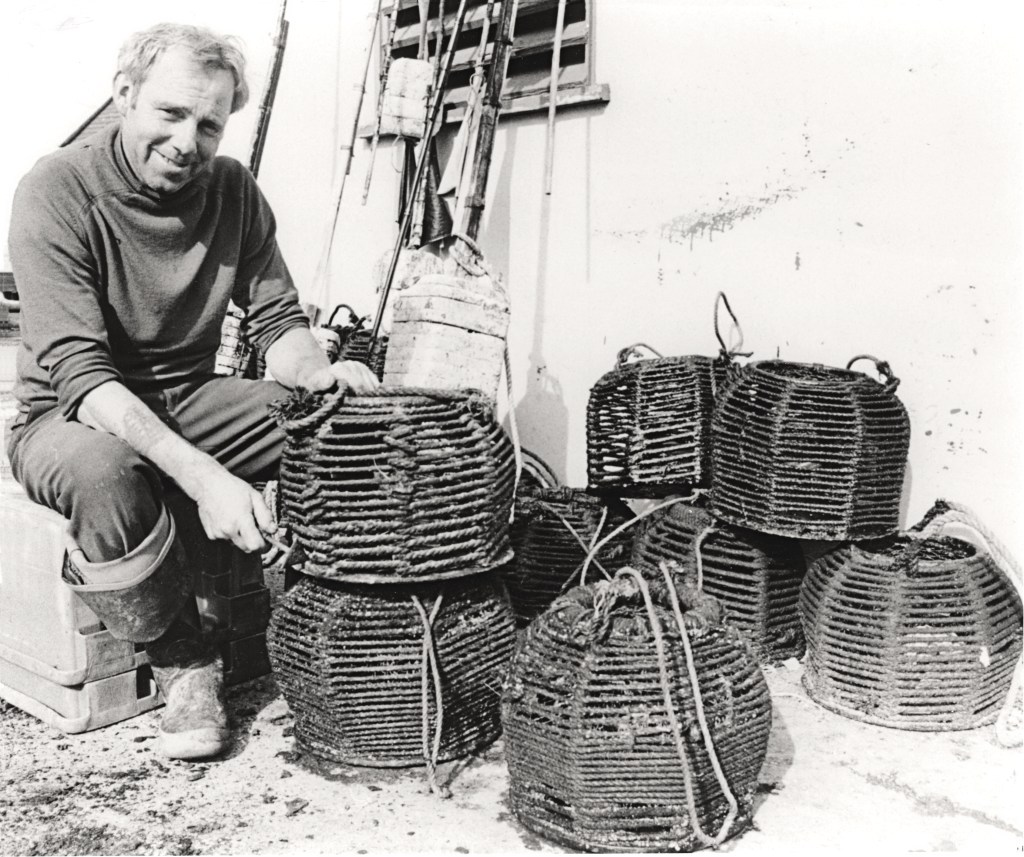

Derrick West mending whelk pots. Courtesy West Family

The restoration of a much loved family boat is a fond reminder of Whitstable’s whelking heritage

by

Floreat

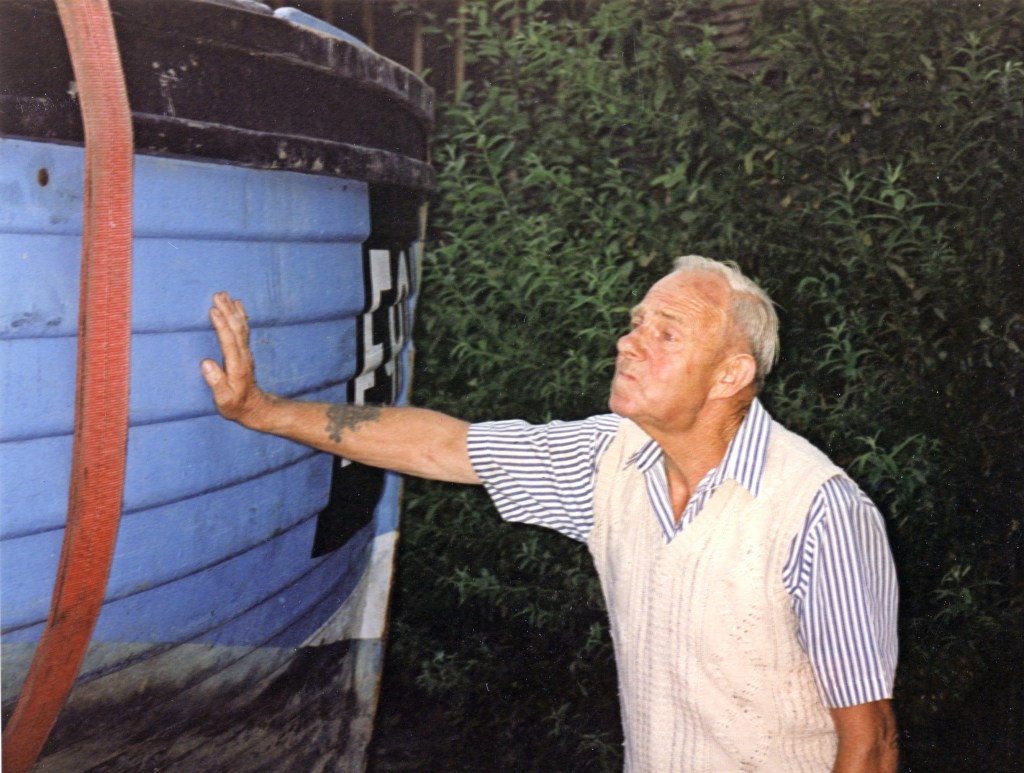

Floreat stands in the museum courtyard. She is a whelk boat, 22 foot long. Made by Anderson, Rigden and Perkins shipyard, Whitstable, around 1948, she was donated to the museum by Derrick West, her previous owner, in 1997. Her Latin name, “Floreat”, means “flourishing”.

She is clinker built, of overlapping larch planks with oak frames steamed to shape, fastened with copper nails, rather like the Viking Longships of yore. Lengths of rounded wood, called listings, are added beneath each plank to make the surface smoother. This is to prevent the whelk pots catching when they are being hauled aboard.

The boat was restored by volunteers Roger Mathews and Dick Church. Roger is a retired carpenter and joiner and Dick was a mariner, fireman and IT technician.

I asked what was special about the boat.

“It’s not special,” said Dick. “It’s typical.”

“But they don’t make boats like this any more,” I said.

“No, they’re made of plastic these days.”

“So it is typical of its era and you are preserving it,” I said. “That’s what makes it special.”

Sheringham

Whitstable is famous for its oysters. Not so well known is the whelk industry. Whelks are predatory sea snails which live on the sea floor in the same areas where the oysters are found. Indeed whelks eat oysters! Prior to the turn of the 20th century, local fishermen used long, hooked lines to catch whelks, which would then be sold as bait. This was called trotting, but it was not the mainstay of their income or their diet.

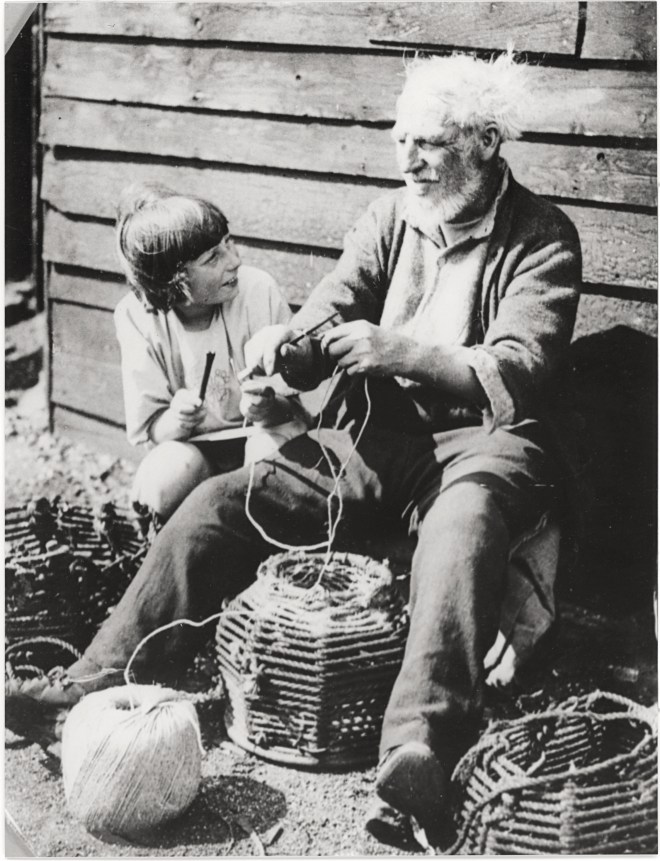

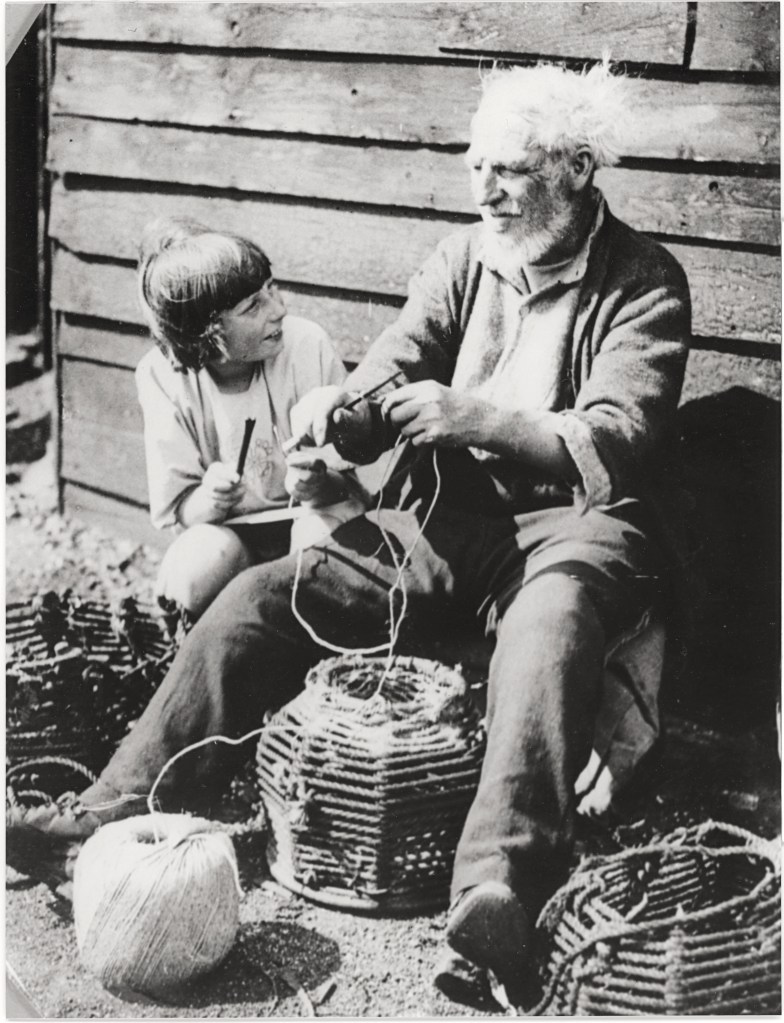

This changed in 1901 when fishermen from Sheringham, Norfolk arrived, bringing with them an innovative means of catching whelks: the Sheringham whelk pot. This is a kind of trap. It has a cast iron base, with iron ribs wrapped in rope, with a hole in the top. The trap is baited. The whelks climb the pot to get to the bait and are then trapped by the crinney net inside (named for its shape like a crinoline skirt).

A number of families arrived at the same time, by boat and by train. These included the Coxes, Wests, Greens, Martins, Johnsons and Bishops. At first there was some friction with the native oystermen. The whelk pots would be laid out in lines, called shanks, on the sea bed in the areas where oysters were cultivated. The oystermen resented the new method and sometimes ropes were mysteriously cut. Eventually, though, the two industries learned to live side by side. Indeed, the families intermarried.

west whelks

Graham West runs West Whelks in the harbour. He is the son of Derrick West, the owner of Floreat, and a descendant of one of the original Sheringham fishermen. He says the reason they left Norfolk was that Queen Victoria wanted the beach for bathing machines. The fishermen used small boats which they pulled up on the beach, and these were in the way. Consequently, they were forced to seek new places to work.

They travelled all around the coast looking for new fishing grounds. Whitstable was only one of the places they migrated to. But there may have been another connection. Many of the whelk trappers were members of the Salvation Army. When they first arrived, Robert Johnson and William West stayed with the Blyth family, who were also Salvationists.

There’s a description of whelk trapping in a book called Life In Kent At The Turn Of The Century by Michael Winstanley. It’s available from Canterbury Library, and here online, at the Internet Archive. Chapter 9 consists mainly of an interview with Bob Bishop, the son of one of the original Sheringham men. Here he describes the uncanny way the fishermen could predict the weather:

“You never had aids or anything to help you. Never had forecasts either in those days. Yet it was strange how they used to forecast the weather and very seldom they were wrong. Lots of old fishermen could look up and tell you what the weather was going to be. Perhaps we’d be off there when I was a school kid and I went with my uncle and my father in the school holidays, the sun would be shining and hardly a ripple in the water. My uncle would say, ‘Come on. Hurry up. Let’s get this haul aboard before it blows.’ And sure enough, once we got home it was blowing hard. How he knew I just don’t know.”

Story originally appeared here:

The museum is run entirely by voluntary staff. Opening hours are 10.30am to 4.30pm all year from Thursday to Saturday.

https://www.whitstablemuseum.org/

Gallery

Click on images to enlarge

Bob Bishop, William West, Charlie Carlton and Harry Day

About CJ Stone

CJ Stone is an author, columnist and feature writer. He has written seven books, and columns and articles for many newspapers and magazines.

Read more of CJ Stone’s work here, here and here.

Whitstable Views

How to use it!

- Make sure you share and like our articles on Facebook and Twitter/X, and whatever other social-media platforms you use. Join us on Facebook here: @whitstableviews

- You can read and contribute articles for free but in order not to miss any, please subscribe to get regular free updates.

- To do so, press the “Subscribe” icon on the bottom right hand corner of the screen. This will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down then reappears at you move it back again!)

- Please engage by leaving comments on the website, rather than on social media. Let’s get a debate going. All our contributors welcome the chance to engage with YOU.

- To all writers out there, we want to hear YOUR views too, so do submit your own articles. Read our submissions page on how to do this: https://whitstableviews/submissions/

- Finally, to keep Whitstable Views alive and independent please donate if you feel able to do so. As little as £1 would help. Details are on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate