Let’s fix the struggling planning system!

by

Dr. Tony Redding

In this article, historian and author Dr. Tony Redding grasps a political hot potato – the need to fix our struggling planning system. He wants more focus on appropriate scale, arguing that development should proceed at a pace comfortable for local communities. Tony is Heritage Lead for the Save Ash Level Campaign, opposing Norwegian state-owned group Statkraft’s plan to build a gigantic solar farm near Sandwich. This would extend to within 160m of Richborough Roman Fort, a scheduled Ancient Monument described by English Heritage as “perhaps the most symbolically important of all the Roman sites in Britain, witnessing the beginning and end of Roman rule.” This article sets out Dr. Redding’s personal views, on the specific case of Richborough and much wider issues arising from what he regards as a degraded planning system.

What the hell is going on in East Kent?

Huge housing projects sprout like mushrooms. Solar farms root anywhere with flat ground and a low-cost link to the Grid. From Westwood to Whitfield, developers are carving up our landscape. East Kent’s remaining marshland is being gobbled up by solar and other energy projects, such as the Cleve Hill solar development under way at Graveney, near Faversham, and the Minster “Sea-Link” converter station.

Drivers stuck in the traffic obstacle course around Westwood are buried in the middle of a housebuilding nightmare. God help a heart attack victim in an ambulance, trying to reach QEQM Hospital during the rush-hour!

Who can argue against the need for new homes and green energy? But we can, and certainly should, argue against housing developments the size of small towns and solar parks the size of small forests. This article is all about the need for appropriate scale. Increasingly, housebuilders and energy developers maximise profits by building on a scale that can suck the life out of local communities. This is not “Nimbyism.” It is a demand for fair play, balance and more respectful development policies.

The threat to Richborough – a national treasure

I should make it clear that I am not a planning expert. Far from it. My introduction to the planning process is recent and came through involvement in the campaign opposing Statkraft’s plan to build a 205-acre solar farm across the unspoilt Ash Level, an ancient landscape and the setting for Richborough Roman Fort. This ill-conceived project will come before Dover District Council’s Planning Committee later this year. Not surprisingly, historians and archaeologists strongly oppose this threat to Richborough, a national treasure and a Class I scheduled Ancient Monument.

As the climate crisis deepens, there is no rational argument against “green-energy”. One might argue about the relative merits of solar and wind, but each must play a prominent part in the energy mix. The real argument here is NOT about the merits of sustainable energy but, rather, appropriate scale and site selection. Left unchecked, the solar majors will continue to run rampant across Kent (and the rest of the country). They are using the Net Zero/national interest arguments to bully their way into big profit schemes, constructing solar parks on a scale swamping local communities.

Watch this video by Nik Mitchell and witness the destruction of East Kent’s remaining marshland:

Why is Richborough so special?

Two thousand years ago, Richborough was an island in the Wantsum, a sea channel separating Kent from the Isle of Thanet. It was the bridgehead for over 40,000 Roman soldiers and auxiliaries, together with tens of thousands of animals, during the Claudian invasion of AD43.

As the Roman legions fought their way across the country, Richborough (Rutupiae) became the first Roman Fort, developing into a major logistics hub with large warehouses and granaries. This base played a central role in supporting four legions as the conquest of Britain unfolded.

Richborough was the gateway to the new province of Britannia and the starting point for Watling Street, the first Roman road in Britain, running from the fort to what eventually became London. Richbrough grew into a sizeable Roman town and port, with an amphitheatre accommodating 5,000 spectators. By the late 3rd Century, Richborough was one of a chain of Saxon Shore Forts, defending the coast against raids by Saxon pirates.

The standing walls of Richborough Roman Fort are an amazing survival. In the early period, the bridgehead fort was protected by V-shaped double defensive ditches and an earth rampart. By around AD60 the fort had developed as a major logistics depot and work on the civilian town began in AD85. The fort and its surrounding landscape were dominated by a massive white marble-clad monumental arch. This 25m tall “quadrifrons” arch, one of the largest in the Roman Empire, demonstrated Rutupiae’s gateway role in the most literal sense. By the 2nd Century, Richborough was a thriving port town, and it continued to function until the end of Roman rule in the 5th Century.

Charlotte Healey, Statkraft UK’s Head of Solar, has made the disingenuous claim that “heritage experts have found no evidence or archaeological record of Roman activity on the site.” Yet prominent archaeologists warn that the threat to Richborough Fort’s landscape setting cannot be mitigated and that the construction of this solar farm could destroy the buried archaeology of the Roman town, which must have extended well beyond the protected area.

In objecting to Statkraft’s proposals, Kent County Council Senior Archaeological Officer Ben Found said: “Richborough is a site that is of exceptional importance in understanding the complete story of Roman Britain. We do not agree with the applicant’s conclusions about the degree of harm that the proposed solar farm would cause to the heritage significance of Richborough … the applicant has not adequately taken into account the contribution that the landscape of the former Wantsum Channel makes to our understanding and appreciation of Roman Richborough. Furthermore, we also do not agree with the applicant’s assessment of the effects of the development on buried archaeology, nor do we agree with their recommendations for how this might be addressed and mitigated.”

Rebecca Lambert, an Inspector of Ancient Monuments at Historic England, added: “We think that solar infrastructure anywhere in the proposed area raises concern and mitigation would not help sufficiently overcome these concerns. Historic England objects to this application because it causes notable heritage harm to assets of the highest order. Harm has not been accurately identified, demonstrably avoided or minimised, and clear and convincing justification for it has not been given … we recommend refusal of this application.”

Richard Taylor, General Manager of the Kent Archaeological Society, commented: “… the proposed development … poses a substantial threat to preserving a culturally and historically significant environment. We disagree with the applicant’s conclusions about the degree of harm the proposed solar farm would cause to the heritage significance of the surrounding area … the long term effects on the area will likely be substantial and detrimental to the historic environment, the local community and the visitor experience associated with Richborough.”

What possessed Statkraft to propose building a large solar farm hard against the most important single Roman site in Britain? The answer is simple. Organisations of this type have tunnel vision and, at the end of the tunnel, they see only money. Ash Level is an area of flat land with a convenient pylon line nearby. Offering the landowner the going rate of £1,000 per acre (x 205 acres) annually for 40 years would be small beer to this solar energy giant. A sum of around £8 million (probably £16 million or more, allowing for inflation breaks) is loose change in the grand scheme of things. If Statkraft get their way, in 2043 (19 years away) visitors arriving at Richborough Fort to celebrate the 2,000th anniversary of the Claudian invasion will be greeted by thousands of solar panels.

Working the system

The Richborough solar farm campaign has become something of a personal revelation. I now appreciate the problems surrounding the achievement of fair outcomes in the world of planning. I had been totally blind to the flim-flam machinations going on around me. Early on, however, I was struck by Statkraft’s name for the Richborough project: “The Little South Solar Farm.” This development is by no means little. It is gigantic – the equivalent of 128 football pitches. In my view, the naming of the project displays a cynical tendency towards misrepresentation.

In early 2022 the developer’s “scoping report” prompted responses from bodies such as Historic England. In effect, these responses amounted to pre-application advice yet were subsequently regarded as satisfying the applicant’s obligations to consult. Later, Historic England was one of several key agencies absent from Dover District Council’s list of “statutory consultees”. The Council corrected this later, following representations. Statkraft finally submitted its full application for the solar farm just before last Christmas – good timing for a low profile!

There was a very short deadline for objections, eventually extended for a brief period in recognition of the “Christmas effect”. Then Dover District Council’s computer system went down and objections could not be registered in the normal way for over a week. In reality, this was all nonsense as that “deadline” was, in effect, no deadline at all. Dover District Council is required to take objections right up to the day of decision! Apparently, the so-called “deadline” is there to encourage statutory consultees to make their submissions in a timely manner. Those unfamiliar with the quirks of the planning process might be forgiven for assuming that a deadline is a deadline. This “Alice through the looking glass” approach to deadlines must encourage many to think they have no time to make representations.

In any event, independent archaeologists are unimpressed with Statkraft’s commissioned archaeological report. They feel it understates the damage likely to be caused to one of the most important historical sites in Britain and overstates the value of “mitigation measures”.

Such issues were examined in detail by Mike Haken, Chair of the Roman Roads Research Association, in his “Assessment of the probable Roman road network in the vicinity of the proposed Little South Solar Farm” (February 2024, Site Report No.SR011). In cases like this, lack of access to the site often causes difficulties. Here, Mike Haken commented: “Whilst the evidence from within the development site is currently inconclusive … the evidence beyond the site itself is incontrovertible: Roman roads from Dover (Dubris) and probably from Canterbury (Durovernum Cantiacorum) combined to run through the centre of the development site in order to cross the Wantsum Channel, either by ferry or causeway, and more probably both. In assessing the possibility of a Roman road crossing the site, the Archaeological Impact Assessment has focused too heavily on a lack of known evidence from the site itself and is not thorough in its assessment of the surrounding Roman road network in order to accurately place the site in the context of that network.”

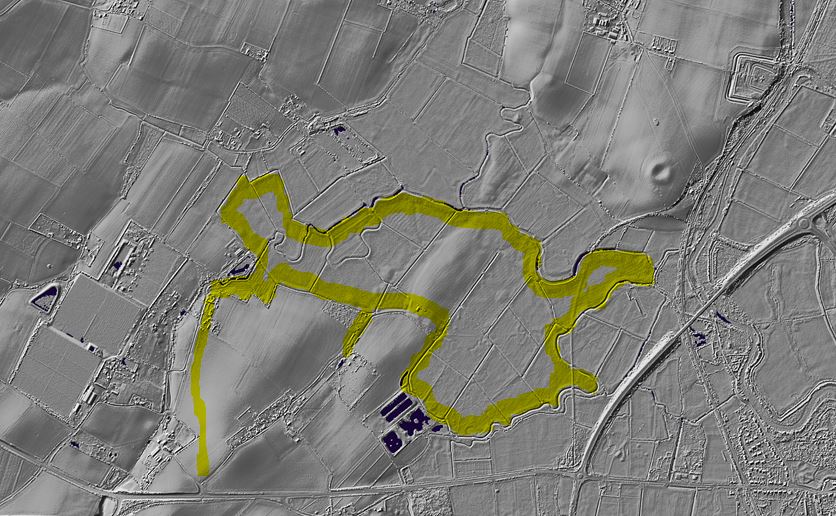

Haken identified the flaws in Statkraft’s commissioned archaeological report. This referenced surveys using technology unlikely to detect archaeological features due to the nature of the soils present. He explained: “The LIDAR (Light Detecting and Ranging) study … utilised a form of visualisation known as ‘slope’, when other visualisations in common archaeological usage produce more easily interpretable results and clearly show potential archaeological features on the site …”

He added that Statkraft’s assessment “shows Roman roads in the area which are actually mainly speculative, but this is not made clear …”

There is no “Grand Master Plan”

Plans setting out future development in East Kent (and elsewhere) are open to manipulation. They may be adjusted or ignored in response to the generic benefits touted (new homes, green energy and jobs, for example). Individual outcomes may be influenced by promises of a new community centre, a sports clubhouse, an access road, or even a “shell hospital” at Canterbury, as promised on one occasion by Quinn Estates in a failed bid to build thousands of homes.

On the green energy front, some local authorities – including Dover District Council – are under immense pressure to meet their over-ambitious targets towards Net Zero. There is an obvious risk that such pressures will overrule all other considerations.

It should be said that East Kent’s problems with a frenetic “Wild West” development environment are nothing special. This is happening everywhere. The problem is not development per se but, rather, development on an overwhelming scale, coupled with often inappropriate site selection. The heart of the problem is the struggling planning system, which is grossly under-resourced. Local authorities and, consequently, their Planning Departments, have been starved of funds. They lack the staff and resources to service an endless succession of ever-larger and more complex developments now changing the face of Kent.

Who is to blame?

It is pointless to blame farmers who make land available for housing and energy schemes. They are offered millions – a fortune for the families concerned but peanuts to housebuilding giants, development moguls and solar energy contractors. If a juicy project is rejected, an appeal almost always follows, progressed with the help of a cabal of very expensive lawyers with a reputation for winning. Heritage has a low value in such circles. In March of last year, for example, a 200-acre solar farm adjacent to the Roman town of Silchester received the green light on appeal, having been turned down by Basingstoke Borough Council in April 2022.

It is pointless to blame developers like Mark Quinn and his chums. Quinn has an armada of around 70 companies, each representing a project. This development machine is fed by a select group of wealthy investors. They are all in the business of making money and we should expect nothing else from them. However, we have every right to be concerned, as developers become ever sharper at playing the system.

It is pointless to blame solar energy providers. The majors have no interest in solar roof systems for homes, industrial buildings and commercial premises. The big money is in gigantic solar parks built on flat land, preferably with a low-cost connection to the Grid. Statkraft and its competitors have only one motto: the bigger the better!

It is pointless to blame local authority planning departments. It would be churlish not to recognise the dedication and public spirit of planning officers in their daily struggle to cope with a tsunami of planning applications for town-sized housing developments and schemes adding to the “solar leprosy” spreading across our farmland. They must also brief Planning Committee members who often lack the time or experience to interpret lengthy, detailed agenda reports on which they are then required to determine the outcome of the application according to planning law.

We are all exposed to feelings of helplessness and resignation, underlined by the bitter comment: “What’s the point of objecting?” We know the planning system is full of holes, and, in many ways, the process itself is a disrespectful charade. But that is the very reason why it is essential to object. Failing to register your personal objection is rather like failing to vote and then complaining about the incoming government.

Yes, it is true that successful developers have the resources and expertise to play the system, and, more often than not, get what they want. If pressed, they will always argue that what they do is in the public interest. In the final analysis, however, we all have a responsibility to hold these people to account, BECAUSE IT IS OUR LIVING ENVIRONMENT THEY ARE DESTROYING.

Central government, of course, is the real villain here. Central government has relaxed the planning process, fostering a “Developers’ Charter” atmosphere (through successive revisions of the National Planning Policy Framework) while failing to ensure planning controls deliver fairly at the local level.

As a result, the solar majors, hiding behind the shield of Net Zero, continue to push the boundaries. Housebuilders continue to build 90% of new homes without solar roofs. Successful developers regard themselves as unstoppable. Here, the motto is: “You can object as much as you like, but it’s still going to happen!”

A Kent Online profile of Mark Quinn (November 2020) gave the developer a platform to complain that he had been “threatened, spat on and told to ‘get cancer’.” This rather revealing story continued: “To his bewilderment, the property tycoon has been bestowed with a reputation as an unscrupulous developer, solely motivated by his bottom line.” Quinn dismissed this: “Do I feel bad about what I do, creating homes for someone like you to buy? No, I don’t. I give people their homes, their safe place. When I show you what I’ve done, you’ll go ‘Jesus Christ, why didn’t he take the money?’ I couldn’t give a damn about being rich; I want to do something I’m proud of. If I’m not proud of it, I won’t do it. I’ve got a four-year old Audi RS7 out the back. It’s probably worth about 35 grand. If I was really into money, I’d be in a Bentley, looking like a prat.”

One thing is clear about Mark Quinn. He has a sense of humour. Every resident at the Quinn Homes development at Grove Park, Sellindge, receives a “Nature Box”, in a move “seeking to make the human world a wilder one”. The box contains a wildflower seed bomb, a bird box, a bird feeder, an insect house and a pond voucher.

Taking control of development

People need homes and power to live successfully in a Net Zero future. Nevertheless, huge developments that threaten to crush local communities must be resisted. It all boils down to appropriate scale and site selection. The planning process needs urgent reform, to strike a better balance between national and local imperatives and also be prepared to uphold house-building figures agreed in Neighbourhood Development plans, rather than allow unbridled continuous development in small rural areas.

The obvious place to begin reform is to levy developers to properly fund the planning process and its policing. For example, those opposing a development should benefit by the full funding of expert reports, to place them on an equal footing with developers. Cash-rich developers could absorb these costs with ease, but expect some stiff resistance! The prospect of a planning system fit for purpose would be most unwelcome to many, as this would require developers to respect local communities.

A question of political will

Killing a cobra is no easy task, but if no-one gets to grips with it, developers of all shades will continue to play the system. This must stop at some point and the sooner the better. So, are there any politicians out there with the courage to campaign for meaningful reform of the planning process?

Deep reform would take years, as there is so much to fix. One useful and immediate innovation, however, would be to make it a legal requirement for local authorities to keep full and accurate minutes of all face-to-face meetings and remote (e.g. Zoom/telephone) contact involving developers. There should be more transparency surrounding so-called Planning Performance Agreements between councils and developers and complete openness regarding who pays for what. The use of privately-paid planning officers raises issues of potential conflict of interest between public and commercial clients which must be addressed if public confidence in the system is to increase. Another reform would involve the presumption that all major developments are subject to Environmental Impact Assessment, with the grounds for any exemption subject to independent scrutiny and report.

Levy funding should provide for effective policing of the planning process and monitoring of compliance with planning conditions. Failure to comply with conditions should trigger severe financial penalties, as non-compliance here strikes at the very heart of public confidence. Another area worthy of reform is the appeals process. Perhaps the system would benefit from the loss of the automatic right of appeal – with the introduction of the need for “leave to appeal”.

Finally, there should be a heavy minimum tariff for any conviction involving bribery and corruption connected with a planning decision. At present, the maximum sentence for an offence under The UK Bribery Act 2010 is 10 years. I believe that 10 years should be the MINIMUM tariff.

There are four relevant key offences under the Act.

- Active bribery – offering to or giving a bribe to another.

- Passive bribery – accepting or requesting a bribe.

- “Consent or connivance” by a director or senior company officer in bribery by a company.

- Failure by a commercial organisation to prevent bribery on its behalf by its “associated persons” – including employees, agents, consultants, contractors, subsidiary companies and joint venture partners. Turning a blind eye to bribery is a criminal offence.

Learn more about corruption risks in local government planning, from Transparency International UK: https://www.transparency.org.uk › publications

This juggernaut has no brakes

Meanwhile, the juggernaut continues unchecked. It has no brakes. The trucks, scrapers, excavators and concrete plants arrive and the voles, newts, birds, butterflies and other wildlife are directed to their new homes, in the “Mitigation Zones”. The flood of new projects continues unabated yet, according to Mark Quinn, there is nothing to fix. There are no constraints.

The 2020 Kent Online article quoted Quinn’s view of the planning process: “Fourteen people decide what happens at a council planning committee. I’m not allowed to talk to them or do anything, but they have to read the evidence that comes to them and decide whether that’s good for the area. That’s all that happens.”

What you can do:

- Contact: tonyr@mulberryr.co.uk

- To object online to the Richborough Solar Farm, visit https://saveashlevel.org and click on the object button.

- Sign this government petition: Introduce new restrictions on solar facilities to protect land and food security

Dr. Tony Redding’s career began as a business journalist, covering energy, international trade and the environment. Later, he founded a crisis communications consultancy with an international client-base. Today, he is a military historian and author. He has a 1st Hons. BA in archaeological studies, from the University of Kent. In 2022 he was awarded a Doctorate by King’s College, London. His PhD subject was the British nuclear deterrent during the Cold War.

Whitstable Views: How You Can Help

- Make sure you share and like our articles on Facebook and Twitter, and whatever other social-media platforms you use.

- Follow the site to get regular updates about new articles when they appear. Press the “Follow” icon in the bottom right hand corner of your screen and that will take you to the option to sign up. (It disappears as you move the text down, then reappears as you move it back up again!)

- Leave comments on the site rather than on Facebook. Let’s get a debate going. All of our contributors are willing to engage with you if you leave a comment.

- To all writers out there, we would LOVE you to make a contribution. Read our submissions page for details on how to go about that: https://whitstableviews.com/submissions/

- Finally you can donate. As little as £1 would help. Details on the donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/